Mark Robinson, CEO of Flint Engineering, explains how the IsoMat could reform energy infrastructure for smarter, greener homes.

With client demand growing for sustainable, energy-efficient properties, smart home professionals must increasingly interface with emerging power systems. Technologies like the IsoMat won’t just change how homes are powered – they may influence how the systems inside are installed, configured and managed. We dig deeper into this breakthrough with Mark Robinson from UK-based R&D company, Flint Engineering.

After running an electronic company, Robinson entered the energy management sector with a sharp eye for innovation. The dotcom collapse in 2000 saw him reinvent the business around sustainable technologies, a move that would define the rest of his career: when he discovered an off-grid multifunctional heating system, the opportunity for storing and replenishing green power was staggering. Robinson was in.

Mark Robinson, CEO of Flint Engineering

“I first saw the system on the roof of the Building Research Establishment (BRE) in Watford, UK,” reflects Robinson. “I realised then that free energy was the future. In some parts of the world, the sun's heat can keep people warm and even cool with the right technology. The IsoMat can do both.”

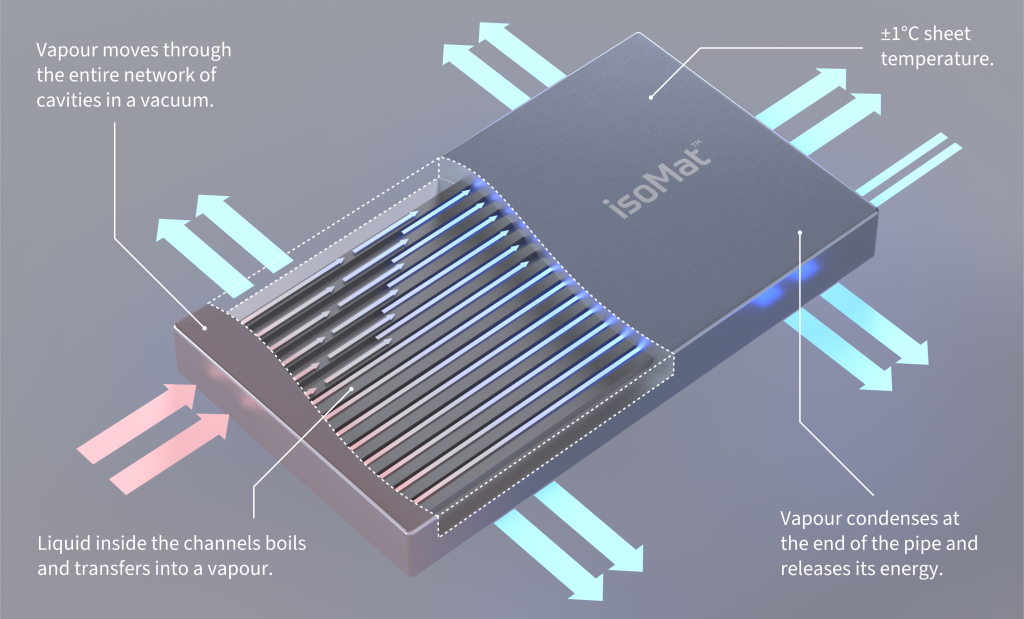

Making international headlines, this flat aluminium sheet uses a condenser to move excess heat to a place where it is useful. The internal structure of the IsoMat moves energy in more than one direction and reduces reliance on other energy sources.

“We found that changes in weather conditions often damage copper pipes in PVT panels,” explains Robinson. “Then the idea for the IsoMat was born. At its core is heat pipe technology, which has been around for 30-50 years.”

First patented in 1942 before official development in 1963, the heat pipe uses boiling and condensation to transfer heat quickly. Advancing the technology, the IsoMat uses a multichannel structure to absorb and move energy two dimensionally. Robinson’s team pioneered the IsoMat in 2013, going on to evaluate it in applications like built environments, commercial refrigeration and EV battery packs.

“The IsoMat can be fitted with solar PV panels to absorb heat and increase electricity generation,” says Robinson. “The vapour then meets the condenser where it turns back into a liquid. The IsoMat can either feed that into the hot water system or a special type of chiller to cool the building.”

Scalable and cost-effective, the technology can generate power independently of an electrical grid. “When it comes to a smart home environment, we have a massive part to play,” says Robinson. “We’re finding the more people get electric vehicles, the more they're needing a smart home connected with other homes in their network.

“If we consider traditional houses and multi-apartment dwellings to be like power stations, we can create an abundance of usable energy which can be used to power people's cars, as well as heat and cool their homes.

“Using the IsoMat, a building can both harvest heat and generate energy which can then be exported to the local environment through a community heating network or smart electricity.”

A revolution is unfolding as global manufacturers and architects look for sustainable ways to meet air conditioning needs in hot climates. “We've been exploring how the IsoMat could supplement roofs or cladding to generate solar power,” reveals Robinson. “For example, we're currently talking to buyers in the Middle East about using it in thousands of homes to tackle abundant sunlight.”

At the cutting edge of energy-efficiency, the systems built around the IsoMat store power without the need for a fuel source. According to Robinson, the IsoMat’s ability to provide long-term savings for developers is also an exciting prospect.

“About ten years ago, architectural consultants in the UK carried out a cost analysis of building a house with an IsoMat roof compared with traditional solar panels,” he says. “There was no difference in building expenditure. Coupled with reduced running costs and energy bills, the IsoMat becomes cheaper in the long term for those building from the ground up.”

This flexible approach appears to be cost-effective against traditional building techniques and cause less harm to the natural environment. Back in 2020, Flint Engineering was part of a £10m research project supported by the European Horizon Fund. The EU's research and innovation funding programme planned to fit IsoMats in seven locations across Europe to reduce C02 production, but was cancelled because of the pandemic. Flint is now moving toward creating these installations commercially.

Elsewhere, the IsoMat could harvest thermal energy “from thin air” to augment existing heat pump technology. “The UK government was keen on using heat pump technology to phase out boilers,” says Robinson. “We think there could be a market where the IsoMat is used on the roof or facade of a building to put energy into the heat pump, making it both cheaper to run and less generative of CO2 because it's not working as hard.”

This thermal strategy captures energy from external air and ground sources to support both heating and cooling. “By harvesting heat on the roof or on the walls of a building, the heat pump can become more effective,” adds Robinson. “These are the next steps that are going to be taken.

“There are some cool architects working on this challenge, one called A Studio who is looking at affordable housing. The team are approaching different UK councils and proposing ways to avoid increasing energy bills in multi-dwelling buildings, up to three or four storeys high – they're suggesting that apartment blocks become like little power stations, providing the local authority with virtually energy free buildings.”

A young company, Flint Engineering is currently going through certification as it explores the largely untapped potential of isothermal energy management. “We’ll be demonstrating effectiveness over the next couple years, proving our concepts with the funding we’re looking to raise in the UK, North America and the Middle East,” says Robinson. “I've no doubt that IsoMat technology will be used in smart homes of the future.”

Why it matters to smart home professionals

Smart homes depend on reliable, efficient power. As technologies like IsoMat reshape how energy is generated, stored and shared, installers need to be ready for what’s next.

Battery storage becomes central: If homes are generating their own power, integrating battery systems for storage and load balancing will become a key part of the conversation.

Smarter systems, smarter scheduling: Clients will expect intelligent control systems that can reduce consumption or shift usage to times when solar or local generation is active.

New install environments: Changes to how homes are powered — from rooftop solar to community networks — may impact wiring, rack locations and system layouts.

Energy credentials sell projects: Green features are no longer just nice-to-haves. They’re part of the value proposition, and clients expect their smart tech to contribute.

Main image credit: Natali_Mis/Shutterstock.com